Upcoming Lecture

Click here for more information about Paragon Management.

- Scott

SimpleDental is dedicated to excellence in clinical efficiency. Scott Perkins, D.D.S., head of research and development, introduces the dental community to products, informatics and systems that simplify and amplify productivity.

Pressure vs. Speed

It has finally occurred to me that "slow" is an inadequate adjective for describing the technique. A much better term would be "low pressure". It is true that a slow injection is a frequent accompaniment to a low pressure injection but it is the low pressure aspect of the BFPDL injection that causes it to be both painless and effective.

Let's think about what is happening when we give such an injection………

Have you ever inserted a needle into some attached gingiva, injected for a bit and then decided, for whatever reason, to withdraw your needle and insert it again in close approximation to the first needle puncture site and injected again? Of course; we dentists all experience the same things over time.

What happens? When injecting into the second site, the flow of anesthesia under pressure from the tremendous mechanical advantage your syringe allows, finds its way into the first puncture and comes shooting back out of it like a squirt gun. If you are not careful, you can just about get hit in the eye with such a stream of anesthesia. What do you do when this happens? If you're like me, you simply duck the stream and inject a little harder, keeping your fingers crossed hoping that enough of the anesthesia makes its way in to have an effect. Or, you poke a third hole and now have two streams flowing back at you.

What can we learn from this? The first thing is this; if a stream of anesthesia is shooting back at you, there is little or no anesthesia that is staying in the patient. The other thing is that the tissue must be very dense in order for such a small hole to act as an exit port for the anesthesia to squirt back through at you.

Let's consider a few other things first and then see if we can come up with some conclusions.

Consider the speed of the injection; if you are in loose alveolar mucosa (which is full of stretchy elastin fibers) a given amount of pressure on the syringe plunger will result in a relatively quick injection. If you are in dense collagen, such as the palate, a given amount of pressure will result in a much slower injection (relatively).

So the speed of the injection varies in proportion to the density of the tissue. The denser the tissue, the slower the injection.

I have been in tissue that is so sense that it seems like my syringe is stuck and not making progress. What we intuitively do when we encounter this situation is squeeze harder on the syringe barrel with the mistaken belief that it is necessary for us to "feel" the anesthesia going in and also to make sure that we get a good dose if it to go. In fact, this is not true. It only takes a very small amount of anesthesia to make this technique work, and it must be administered under high enough pressure to make its way into the tissue, but not pressure that is high enough to rupture and injure tissue.

What we know

We already know a few things about the BFPDL injection technique.

Here are a few conclusions that I have made while observing many dentists over time in my hands-on workshop.

Perception vs. Reality

A very large percentage of general dentists, in fact, the majority of GD's are incredibly heavy handed. Even when admonished, they just cannot help themselves. Recidivism is the rule, even when having some initial success; before long, they simply revert back to their old habits and then wonder why they just can't seem to make the technique work for themselves. It's easy to become frustrated with the technique when this happens.

This is a natural human trait and should, in no way, be seen as a criticism. On the other hand, it should be recognized. It is only through recognition of this phenomenon that true change can be allowed to take root and flourish.

The Consequences of a High Pressure Injection

High Pressure to tissue, injures tissue. It is responsible for necrosis, paresthesia and pain. After all, pain is a warning of tissue injury. Tissue injury is often caused by high pressure over a short time span.

Connective tissue is ruptured, cell injury and cell death result. Histamine release occurs, etc.

The average dentist (including myself in the past), is to lean on the syringe up to the point where the carpule actually bursts inside of the syringe barrel.

The dentist is interested in delivering a bolus of anesthesia. He is in a hurry. Since time is relative, the dentist thinks that he is saving time by giving a block, which is fairly quick, and then moving to the next op. In fact, once a dentist leaves an operatory, any number of time delays can occur not-with-standing the transit time, hand-washing and glove change. Conversations, forgetfulness, etc. may occur. Greetings, observations of points of etiquette, reviewing treatment and x-rays, etc. must all occur. Repositioning your chair, focusing on the tooth, retooling, etc.

Time slows down when you are giving a long injection. What takes a mere two minutes, instead seems like it takes forever. The beauty of these higher pressure (but not too high of a pressure) injections is, that they are incredibly efficient when compared to the alternative chair-hopping paradigm. On average, the time spent attaining anesthesia is a fraction of what block anesthesia is.

What I have Observed Over Time

I've been fortunate enough to be able to observe quite a few things first hand when it comes to the behavior of dentists since I instruct dentists on a regular basis here in Houston. It's given me some insight and perspective on the behavior of dentists.

A big part of what I teach is endo. I use endo as an example of heavy handedness because it is easy for me to directly observe the force and length of time the typical dentist will apply to a file in a canal. The average dentist is heavy handed, IMO. They drive the file in the canal and leave it there too long. To me that's very scary because I know that the likelihood of file breakage is high; in fact it is inevitable.

The same is true with injections. The average dentist is putting too much force on the trigger of his or her PDL syringe because it is not real to them just how slow the injection needs to be together with the fact that they are in a hurry and feel the need to get going at all costs. The perception of time varies wildly.

Consider the typical argument with your wife over your time getting home. She will round off to the nearest half hour or fifteen minute increment in her favor, you will round off time in your favor. It is a natural human instinct. We are all egocentric to a degree (hopefully short of being sociopathic). If you average the two times, it will usually come out close to the true time (all-be-it slightly in favor of the wife's point of view, on average).

There is a distortion of the element of time in the mind of the general dentist.

The Cortical Plate

The cortical plate is thin in the area of the interproximal area. This is easy to demonstrate; the next time you have the opportunity to anesthetize a tooth that is next to an edentulous area in the mandible, give an intra-osseous injection directly on top of the ridge. You will find that it is very easy to penetrate the cortical plate in this area.

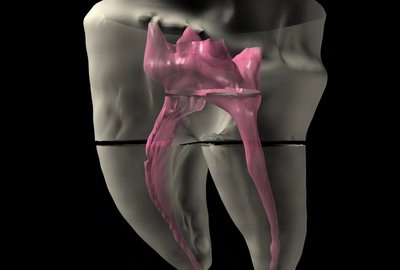

Now consider this; the cortical plate is very thin in the area between two adjacent teeth even when there is not an edentulous area. If you penetrate the interdental papilla with a short needle in a PDL type syringe and drive the needle into the col area so that the needle lands directly into the bone at the nadir of the col, and you apply pressure, it is sometimes possible to penetrate the cortical plate to a degree. In any case, it is usually possible to gain good back-pressure in this area. Now, inject very slowly. You will achieve good anesthesia from this injection and you will achieve anesthesia on two teeth.

When giving a standard BFPDL, many ask me if it is necessary to give an injection lingually as well. The answer is no (the vast majority of the time). The anesthesia penetrates quite readily to include the tissue lingually even from a buccal injection.

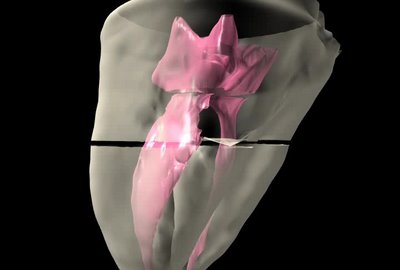

A PDL technique and even a col injection are both, almost certainly, an intra-osseous technique since the anesthesia flows through the highly vascular medullary bone making its way down to the apical foramen where the nervous tissue and vascular system supply the tooth. There have been a few studies performed with dye that show this to be the case.

An Efficient Beginner's Strategy

If I was just starting out and I wanted to master this technique, I would begin with a block and then start with a BFPDL and then proceed to a col injection technique. You're going to be able to give a block over a period of time of one minute, a BFPDL takes about two minutes. A col technique takes about another two minutes. If the BFPDL technique is successful, you are able to begin your procedure without leaving the chair in about three minutes without the col injection and about five minutes with the col injection, which beats the socks off of a block technique in terms of time of onset of profound anesthesia.

You gain not only the time that you would have spent by a longer injection but also all the time that is typically lost with a block injection technique.

So here are some succinct conclusions:

1. Many times, dentists think they are giving slow injections when in reality they are not.

2. The injection is based on pressure more than it is based on speed.

3. When in dense collagen, the speed is almost certainly slow.

4. Resistance created by a stuck plunger needs to be obviated by injecting a drop or two of anesthesia before you start the injection, otherwise you will not be able to differentiate between resistance to the injection site itself and the added resistance of a stuck rubber plunger.

5. You may inject into the col area.

6. It is not the amount of anesthesia emptied out of the syringe that counts, it is the amount of anesthesia that enters the tissue and stays there that counts.

7. You may inject in the LFPDL. Many claim better results when injecting here than when using the BFPDL.

Here's my advice. Don't give up on this technique. Of all the efficiencies I have written about, developed or improved, rapid, predictable, painless anesthesia is the most critical of all for the efficient dentist.

Hans was looking a little too eager to give me a buccal furca PDL the other day at the workshop so I opted for a little Nitrous.

Hans was looking a little too eager to give me a buccal furca PDL the other day at the workshop so I opted for a little Nitrous.

You done good Hans. I never felt a thing. Not a speck of post-op pain either.

You done good Hans. I never felt a thing. Not a speck of post-op pain either.

When I analyzed the crown procedure, I found efficiencies that would cut time by a factor of four.

Then I decided to tackle endo because endo stressed me. I didn't think I could be as effective because of all the endodontists who study and lecture on the technique. I was wrong. I immediately found efficiencies that they had overlooked that slashed their times in half.

Next I took on prophy's. I was at first sad because I could only reduce this procedure by 20%. Then I analyzed the potential net profit increase that should result. It was $100,000 of net income per year! I hadn''t considered that we do a volume of this procedure so even small efficiency gains add up.

Off and on through all this, my mind wanders to the composite procedure. I look at everything out there I can find. Maybe there''s some hidden secret I've overlooked. Also, I apply my mind to developing a new product or sequence that will create efficiency.

The composite filling is one of the most interesting phenomena in dentistry from a procedural as well as a philosophical aspect. How we do composites, when we do composites and what materials we use to do them with reveal a lot about us.

We do composites more than any other procedure. Most of us when we do a crown or an endo for a build-up. Sealants are a composite. We place them in class IV lesions.

Careers have been built out of lecturing about composite.

It is, by far, the most challenging material we have to work with. It is highly technique sensitive and time consuming to do right.

The proximal box is more difficult to perform than crown preparation or endo access. It requires more fine motor control and carefullness.

KaVo even has sonic tips designed to shape uniform proximal boxes.

Should you use a rubber dam?

Should you do a composite at all?

Should you use caries indicator?

Should you use a low speed?

Should the axial walls be smooth or does it matter?

Which material to bond with is an area of great discussion.

Which device do you use for forming the proximal aspect (there are so many contraptions for this) and how in the world do you keep from getting a diastema?

What light should you cure with? LED? PAC? Etc. How long should you cure?

Should you layer it?

What about dual cured?

And the most challenging part of doing a composite.......Shaping and finishing. What a hassle. Now you're doing a lab techs job. And you complained about their anatomy.

Composites are labor intensive and composites deserve a very long discussion in order to ferret out all the advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches.

As it turns out, one of the most overlooked aspect of the composite is the environment that you placed it in. That''s another story.

It seems to me that more people have taken a crack at ways to do composites than any other restoration.

No huge efficency gains have popped into my head yet but I''m not through analyzing by a long shot.

I predict that I will be able to save some time. Not the dramatic, sensational and unbelievable time savings that occurred in the 15MME and 15MCP but significant time will be saved. Enough to make life a little easier and lift the cieling on productivity a little higher.

Composites may be divided into 3 categories: Occlusal, proximal and anterior. Each has a different approach and a different set of problems.

Proximals are the most complex.

Check back with me on the composite. Composites are going to take awhile.

The phobic patient is sucking in a deep breath and/or hyperventilating while you apologize and inject with them white knuckling your arm rest, beads of sweat visible on their upper lip and brow furrowed like a disc harrow ran over it.(sorry, it must be the farmer coming out of me)

Then half the time they don''t take and when they do it takes forever and even if their lip is numb a percentage of the time you drive the bur into their tooth and they recoil in pain and you apologize again and start explaining how it''s not your fault because if their lip is numb their tooth should be numb but not always because of auxiliary (or collateral) innervation and it''s not really your fault but you feel guilty anyway.

The patient is in some sort of misery trance and is probably not hearing a word you say and if they do they can''t respond to you anyway because of their complex phobic/accusation mental make-up that puts you in the category of one who might be met in hell some day.

It doesn't matter that you are effusive in your remorse for putting them in torment, they have no capacity to even respond to you.

So you pull out your ligajector and shoot them with Lidocaine (pre-articaine), and give them another block or two (the dense pack technique) we used to jokingly call it in dental school. We shoot high, we shoot low, the patients cheek is full of holes.

The patient senses our inneffectuality and we are perfectly aware of it ourselves. "I must be the worst dentist there ever was. The most incompetent. I must have been sick and absent the day they taught mandiblular blocks." You think to yourself.

You try the Akinosi technique, you try the Gow Gates. Nothing works. You are sitting on needles as you attempt to drill again, just waiting for the patient to abruptly scream sending you gasping for breath.

Sometimes, long after you’ve finished the treatment the patient declares, "I think I''m numb now!"

Mandibular Block Gone South Syndrome sets in. (No offense to my venerable Southern brothers).

Why, after 18 years of practice do I continue to be surprised by a patient who starts to hyperventilate and groan and whine and carry on like I’ve tortured them immeasurably before I’ve actually touched them?

The real clincher is the patient who makes you sweat through the entire process leaving you wrung out like a squeezed rag and feeling at your absolute lowest. You would apologize only to hear the patient say, “Oh no doc, that was great, I didn’t feel a thing!” “Then why on earth did you subject me to such misery!!” You want to shout. But you don’t shout, you just look back at them with disbelief that they could have carried on that way making you completely miserable while they evidently received the most gentle injection of their life.And you imagine to yourself that all your colleagues must be perfectly adept at giving mandibular blocks and you are just deficient and incompetent and probably shouldn’t even have been allowed to graduate from dental school. In fact the state board of dental examiners could come busting in at any minute to strip you of your license and drum you out of the profession.

We sweat as much as they do. We really do. And we use nitrous oxide, in which case we have a “high” phobic or perhaps Valium in which case we have a “drousy” phobic or we use “conscious”sedation or even total general anesthesia in an attempt to deal with the trauma of a mandibular block. (actually zapping them with a little Halcyon is the best fix we’ve ever come up with.)

The patient holds up their hands like they are telling a “Big Fish” tale and say, “The last dentist came at me with a syringe this long!” (the gesture is about a foot or so long) and in their mind they are telling the truth.

Now maybe you’ve never experienced what I’m describing, and your mandibular blocks take every time and you’ve never had a single solitary case of trismus or paresthesia after giving a mandiblur block and you are in a state of shock to hear me go on about mandibular blocks like I’ve been doing for so long now…………………………..but somehow I doubt it.

Can you imagine the guy who got the guts to try the world’s first mandibular block? This dude must have had some cahonas. “If you don’t mind Mr. Smith, I’ve got this theory that if I can stab deep enough and strike solid bone,( I’ll know that when my needle flexes like a recurved bow you know), and then inject a good dose of Novacaine in the area that I just might hit the mandibular nerve just before it goes diving into the mandibular foramen and then you’ll be a lot more comfortable while I’m drilling into your dentinal tubules. And by the way, while I’m at it, excuse me while I stick you again and give you a good old “long buccal” just in case I wind up wrapping your cheek around a 557 bur later on during the drilling process. If you’re really good and sit very still, we’ll probably be able to avoid this. Maybe.

Rats! I’ve done it again. Rambled on obsessively about mandibular blocks and my personal frustrations. Oh well.

To make a long story longer. Shooting a buccal furca in the PDL is quick, predictable and painless if you do it right. The tooth goes down, the patient doesn’t suffer and you can get through your procedure without a hassle and no wait, no suspense. If I want suspense I’ll watch an Alfred Hitchcock movie.

I called for a volunteer. A female dentist, Elizabeth Lee raised her hand. I pulled a chair into the middle of the aisle and asked her to sit down. I shot her in the PDL and asked her if she felt any pain. She said, "No pain." I asked Chris Griffin, my host dentist, to spray endo ice on a cotton roll. It looked like a fire extinguisher the way Chris sprayed it. Vapor was smoking off the cotton roll. She felt sensation, I had missed the buccal furca, (try giving an injection with no light with the patient sitting in an auditorium chair, not easy). I re-injected and tried again. This time, no sensation, no pain.

Then I Popped her in the palate with my relatively painless Palatal anesthesia technique. She reported negligible pain.

The cotton rolls take care of soaking up the anesthesia. The taste of Septocaine is absolutely repugnant. Do everything you can not to let your patients taste it.

I use it to numb one tooth at a time but the way Septocaine tends to travel it frequently will numb adjacent teeth.

The injection lasts 30 minutes to an hour usually.

I developed the refined technique only about three weeks ago.

I traded shots in the palate with three dentists that month. Howard Glazer, Peter Norris and Chris Griffin. I call these guys my blood brothers. I have taken a shot to the PDL one time, (just for practice)

In my hands-on-workshops, I shoot the dentists in the palate. I still prefer the palatal injection when working on the upper.

Rapid, painless anesthesia is key to efficiency.

In a modern practice, digital radiography is essential

The day I dumped that blasted machine in the trash was one of the most triumphant days of my life. I said goodbye to developing time, processor maintenance, duplication time and pulling charts to obtain x-rays. Digital radiography is an information tool that allows you to share information with a patient in a way that has never before been possible. I never considered that x-rays were a case presentation tool until I got digital. Patients can absolutely see what you are talking about. I have 17.5 inch flat screen monitors in my operatories and patients turn their heads to see their images pop up on the screen. They can now easily see decay, bone loss, wisdom teeth, large fillings, tooth wear and periapical radiolucencies.

X-rays were never a very good patient education tool because of their small size. How many times have you pulled a view box off of your counter top, handed it to the patient and said, “Mrs. Jones, can you see that shadow right there? That’s tooth decay and we need to fix it.” Then Mrs. Jones says, “Where?” and you say, “Right there. Do you see it?“ and she says, “Not really” or “I think I do.” “Wait a minute Mrs. Jones, let me get something smaller to point with.” You search around for something. You find a perio probe or a cotton tipped applicator. “Now look Mrs. Jones, do you see it now?” Mrs. Jones squints her eyes. Her brow wrinkles up. She says, “Oh yeah, I see it now, right there?” “No Mrs. Jones, that’s the interproximal space, I mean it’s just space, you know space between your teeth. Space between your teeth is nothing to worry about, we all have space between our teeth. I’m talking about that shadow in your tooth right there. Right there.” You are pointing with your stick. Mrs. Jones smiles weakly and shrugs or nods. “O.K. I trust you, what should we do about it?“

Have you ever stopped to count the motions involved in loading film in and out of a holder such as a Rinn? There are multiple repetitive motions involved. With digital x-rays, the sensor never leaves the mouth. You just move it around. Digital radiography allows your hygienist or dental assistant to stay in the room with the patient. Patients do not like to be left sitting alone and bored in the dental chair. When a hygienist leaves the patient to go to the lab, there is a greater likelihood that she will run into another employee and start a conversation. In addition, if there is already another staff member feeding x-rays through, she’ll have to wait her turn leaving your patient alone and increasing your chair time.

How many times have you ever seen films go into the automatic processor and never come out, or the processor break down? How many times have you run out of fixer or developer and discovered the problem only after ruining x-rays?

Manufacturers are quick to explain that digital radiography greatly reduces radiation exposure, but really how important is this feature? There is significantly less radiation exposure to the patient because it takes less radiation to expose a digital sensor than it does to expose silver halide crystals. Whether decreasing radiation to the patient is significant or not in the amounts we use, patients perceive decreased radiation as a benefit and they will appreciate your progressiveness and concern for their well-being.

I wish I could count the times that a box of pano film has been inadvertently exposed in my office. Thankfully, I have a merciful staff that shields me from this knowledge in order to spare me unnecessary grief and consternation. Switching to digital radiography means you will not have to deal with ordering film, developer or mounts.

Imagine that you could put a video camera above a dental office and monitor the traffic in and out of a dental laboratory every day. If you measured in miles, the trips to handle film, how many miles do you suppose it would be? Throw in the time it takes to phone in orders for supplies and unpacking, stocking into the lab cabinets and then again, stocking film into the operatories. A significant amount of time and distance each month is spent performing these tasks. Now imagine the sudden elimination of all that time and travel. What an impact!

With digital, no mounting is required so you do not have to expend time training an assistant to orient the dots, mount, troubleshoot bad x-rays, maintain film inventory or order chemicals. That’s what digital radiography has done for my practice.

With digital radiography, you shoot and receive immediate results. If there is a problem with the x-ray, everything is still in place and you re-shoot.

Consider shooting check films for endo. With film, you pull back the rubber dam, you insert your film holder trying to work around a wild tongue or a shallow palate, you align your x-ray head, push the trigger to shoot the x-ray head, take the film out of the mouth, put it through the x-ray processor, put the rubber dam back on, push the x-ray head back, let the dental chair back down into working position and then pray fervently that you got the shot. “Rats!” You missed the shot. Drag the film holder back out, put the lead shield back on, put the thyroid protector back on, put the film holder back in the mouth, realign the x-ray head, shoot, repeat all the other steps including praying and even then you may find yourself repeating the entire process. Even if you get the shot, a canal might overlap another one, a zygomatic arch might be in the way, the rubber dam clamp might overlap the apices and file tip, etc., etc. (I am beginning to sound like Yul Brynner in the King and I.)

Now, consider endo shots using digital radiography. I can even take my own shots now. The first shot is lined up. I depress the button on the x-ray machine and hear a brief blip. Within three seconds an image appears. During this time, the x-ray head is still aimed at the same spot, the rubber dam is pulled aside and the patients head and the film holder remain exactly as they are. All references are intact. Using x-ray films, all references are lost - you only have your memory to rely on. If you miss the shot, it’s easy to see how to make the correction. It’s so fast to shoot another shot, and the radiation exposure is so low, I don’t mind taking several shots in order to elucidate as much information as possible as to exactly where those file tips are in relation to the apices of the roots you’re working on. Quality is increased while your stress is reduced and you will feel good about what you’re doing.

One of the major considerations about switching to digital is economics and the payback period. Applying the time savings already discussed, let’s apply some real numbers to the labor and materials costs.

Time savings resulting from immediately obtaining an image, with no developing or mounting time, can easily save you 10 minutes per patient. That’s up to 80 minutes per day or roughly an hour-and-a-half. If you calculate a hygienist’s hourly rate and multiply it by three, you get $90 per hour. Multiplied by the time savings means you save $135 per day in chairtime and labor by using digital x-rays. Now, you have created capacity and can now fit at least one more patient per day into your schedule. With an average hourly rate of $100 per hour, you have just increased your production by $235 per day and your hygienist still has a spare 30 minutes to increase your practice’s daily production revenue even more! Even if you calculate the savings based on a four-day workweek, the savings still amounts to roughly $3,500 per month (not to mention the savings from supplies, increased case acceptance, goodwill from value added service. Plus, the amount of money saved from film costs, duplicating, chemicals and maintenance.)

So, let’s assume you save $3,500 plus in production and another $3,500 in supplies. That’s $7,000 in extra revenue per month. If you’re doing endo 15 cases per month, that equates to 30 hours of doctor production time saved in a year. If your average production is $250 per hour, that’s another $7,500 per year in increased revenue. Now what do you think of digital radiography?

Digital radiography is essential if you’re going to go paperless. Once you go paperless, you will have eliminated one of the most arduous and time-consuming processes in the office - chart pulling and filing. Do you know how much time accessing and filing charts takes in your practice each day? Let’s assume your staff pulls about 20 charts a day. Once pulled, the charts are handed back and forth between the front desk and the operatory. Sometimes the charts are lost. How many miles of walking do you think occurs from just carrying charts back and forth, in addition to locating lost files? Let’s take the figure of two hours per day of chart handling in one form or another. A $20 per hour assistant times three in order to get overhead expense, that’s $60 per hour or $120 per day. That’s about $1,800 per month in chart pulling. That kicks the figure up to about $123,000 per year.

Digital pan:. . . . . . . . . $80,000

Digital sensors x 3: . . . $18,000

Total:. . . . . . . . . . . . . . $98,000

Tax write off:. . . . . . . . $30,000

Total:. . . . . . . . . . . . . . $70,000

Now, how can you justify the enormous cost of switching to digital radiography? Well, let’s look at the cost of owning digital: That’s right - digital can completely pay for itself in the very first year if you make use of all its benefits. Although I’ve only had digital in my office six months, I anticipate saving $100,000 my first year.

Have you ever experienced an insurance company stating they never received a patient’s x-rays? Personally, I’ve had insurance companies that have stated that many times for an individual patient. Not only is this situation extremely frustrating for you and your staff, it costs you additional money! Some dentists even compensate for these prevalent problems and shoot doubles to prevent a retake. But think about this...once your original is ’gone’ you now have to have the second copy duplicated to maintain a file copy for you records in the event this situation happens again. Have you ever stopped to calculate the cost of having an x-ray duplicated? And, the maddening thing about it is that the duplicated x-ray is not diagnostic anyway. First you have to pull the chart. Then you have to find the x-ray duplicating cassette. Next you have to find some film, remove the film from its container and put it into the cassette with the fresh film. Then you expose it and finally run it through the processor. The whole process takes about 10 minutes. Not only do you have to count the time and expense of an employee duplicating an x-ray, but you also have to count the time lost that the valuable employee could have used doing a task that had something to do with serving your patients. Who pays for duplication of x-rays? Does the insurance company? Does the patient? The answer is a resounding NO! The doctor pays for it. And why? So some selfish insurance company can clog up the everyday operations of your business to enhance their non-value added profits.

With digital x-rays, when the insurance company reports a missing x-ray, you simply poke a few buttons on your keyboard and a new one prints out of your 1200 dpi laser printer and you’re done. The whole thing takes less than one minute. It’s easy and it’s quick.

So, can you afford to adapt digital radiography into your practice? As a fellow colleague, I’m telling you, you simply can’t afford not to!

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the refugees came pouring in here in

Jerome Smith recently invited me to join him along with 9 LSU dental students to work in a charity clinic in

I accepted. The charity clinic began with mostly extractions. It has been there long enough to reduce much of the extraction “volume” and now restorative work is performed at an increasing rate.

Our purpose was multi-faceted. LSU’s dental college offers endo education to its dental students by elective during the senior year. There are only 15 slots available for the elective and approximately 60 students. As a result, many LSU dental grads have no endo experience.

Our goal was to teach these students how to perform endo in an efficient way. I regularly hold workshops here in

Jerry is a first class educator and efficiency expert and almost certainly has superceded myself in terms of clinical application of clinical efficiencies, particularly in the area of case presentation, practice management and implants. I cook up all the wild hair brain schemes and Jerry implements them.

There were only 6 chairs so I brought an additional Military style dental chair and a “camp” style lounge chair that allowed us to perform exams in order to diagnose and “triage” the patients. I also brought along portable compressors and units and other supplies and equipment that I ordinarily use for my workshop so that we could increase the amount of dentistry performed.

We provided training the day before we see patients and every evening we reviewed cases and provided additional didactics.

Actually, the course was not all that different than the one I give regularly in

In designing my course, I practiced teaching novices by teaching some of my staff to perform endo. In fact, in my workshops we teach the assistants to do endo and we teach the dentists how to be assistants. My technique is driven by my assistant. Ordinarily the assistant’s brain is "off" during endo (that's why they tend to doze off). We flip the switch in their brain to the "on" postition.

I think it's crucial that the doctor understands the assistant's perspective and vice versa; only then do they have the potential to achieve maximum synergy.

The doctor's time and effort during the procedure is reduced and the assistant's time and effort in increased. Assistant's prefer this, by the way (so do the doctors).

Efficient endo is a team effort.

I brought along my 2 oldest boys who assisted and performed photography. They have helped me in my dental office over the years and some of the photography that has appeared in my articles was actually performed by Riley who just turned 13. My son Michael, who is 17 has also been a valuable asset. Michael seems to be able to tackle just about any problem.

Life has gone by so fast, and I really enjoyed being with them in such an environment.

Both the boys had visions of surfing in

2 junior

I wanted to expose bright, motivated, ambitious young engineering students to dentistry so that they could help me develop new products and communications. So far I have been very impressed with their work. In addition to Tim and Alex, I hired an Electrical Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Chemical Engineering and Physics students all from the same class.

The third world needs help. Jerry and I have a dream that we can bring clinical efficiencies to the third world and provide good hands on training to dentists from the

If the current dental force in the third world could perform twice as much dentistry through simple efficiency principles, dental healthcare could become available to a wider population. It seems like a noble goal.

Spending time with my good friend Jerome Smith, the students, the patients and my college boys and sons insured a great experience for everyone involved. I'd like to go to

The second you touch a bur in order to re-use it, you have just lost money. Forget about attempting to calculate the hourly wage of your employee and equating how many burs they can sterilize in a given amount of time. That is a calculation that does not yield a true answer.

There are many other factors that weigh in on net profitability and the most efficient way to use burs.

I sell the Samurai. It withstands autoclavings. If dentists would like to re-use it, they most certainly can. It is, in fact the only dentate bur I know of that can withstand autoclavings without being severely degraded.

Even so, I wouldn't recommend re-using any bur with few exceptions. Re-using burs is a costly way to perform dentistry as well as being a more frustrating and time consuming way